Monday, May 21, 2018

Part of a month-long celebration of Ron Lesser’s artistic legacy

By J. Kingston Pierce

The Lesser Look: Bringing a Taste for Classical Realism to the Realm of “Sexy Crime Babes”

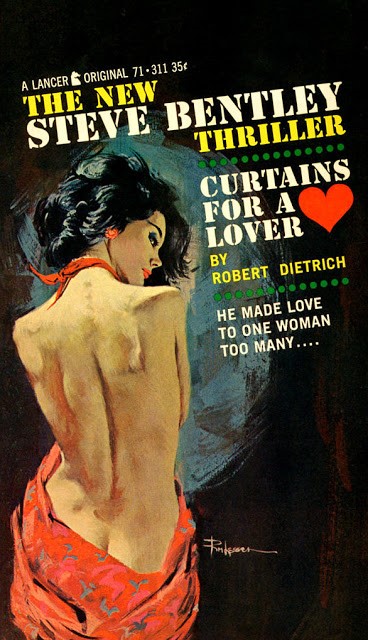

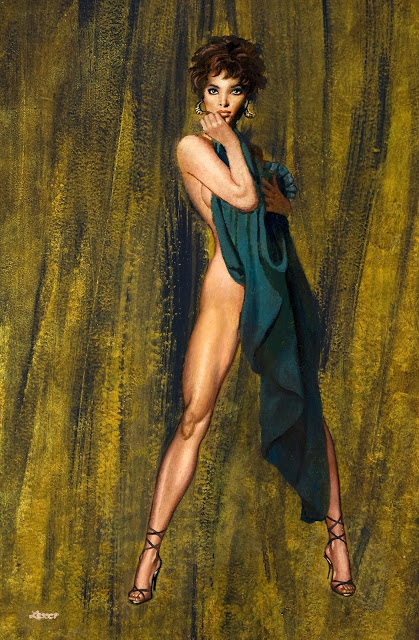

Curtains for a Lover, by “Robert Dietrich,” aka E. Howard Hunt (Lancer, 1962). This was Hunt’s seventh novel starring Washington, D.C.-based accountant-cum-detective, Steve Bentley. Enjoy Ron Lesser’s original artwork here

When I asked Charles Ardai, the editor of Manhattan-based book publisher Hard Case Crime, for a comment about once-prominent U.S. paperback artist Ron Lesser, he was quick to respond.

“I’m delighted you’re going to be featuring Ron on the site!” wrote Ardai, who has purchased at least three paintings from Lesser for use on Hard Case releases over the last decade. “He’s a terrific guy, and one of the last painters of the paperback-only era still working today. Like his contemporaries, but unlike most current painters, he’s got the training and skill at draftsmanship and anatomy to give the people he paints that extra degree of realism that makes classical painting just leap from the cover of a book. He works traditionally, not digitally, and that shows too: you can tell when a painter is manipulating pigment rather than pixels. You can see Robert McGinnis’ influence in his work, and at his best I think his work is in that league, which I mean as the highest possible praise—very few painters have ever come close to McGinnis, even at their best.”

Lesser isn’t nearly as quick to toot his own horn when I ask him how his artistry compares with that of the numerous paperback illustrators he competed against during the mid- to late-20th century, most of whom are no longer around. “I would sound like an ass if I answered that question,” he remarked in a recent e-mail note. “I am not that conceited.” Lesser later explained that he’s talked occasionally with his agent about assembling a handsome book-length collection of the paintings he has devised over the last half-century, but jokes that there may be no market for such an opus. As an alternative, he suggests “maybe a pamphlet, about three pages [long].”

(Right) Ron Lesser

But really, three pages wouldn’t even begin to tell the story of Lesser’s influence on what was once a thriving business in paperback-cover art, much less elucidate the many successes he has seen since that market dried up.

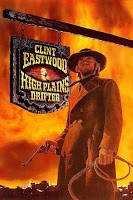

As early as his grade-school years, he developed an interest in drawing and painting, which eventually led him to enroll at the city’s eminent Pratt Institute, and subsequently at the Art Students League of New York (ASL), where he studied with Frank J. Reilly. As Lesser’s Web site explains, “Reilly taught drawing, painting, color theory, and educated Ron in what he needed to learn most—the fundamental principles behind creating art.” Lesser fashioned his first paperback cover illustration while he was still an ASL pupil; he continued to generate such canvases into the 1990s, by which time he had produced “several thousand paperback covers”—the majority of them for crime and Western novels—and become one of the field’s foremost practitioners. Meanwhile, he took on assignments painting advertisements as well as Hollywood movie posters, the latter enterprise resulting in his design for such iconic placards as those plugging the 1973 picture High Plains Drifter and the James Coburn/Kris Kristofferson flick, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, which also debuted that same year.

Keeping busy was important to Lesser for more reasons than one. He had a family to support, having met and proposed to a woman named Claudia when they were both 18. After their marriage, the couple bore a son, and Lesser enlisted Claudia periodically as one of many covers models he used over the years. Sadly, Claudia passed away in 1998.

Book and magazine illustration saw its heyday from about the 1930s through the 1970s. After that, publishers started cutting back on the expense of commissioned paintings. Cheaper photography encroached on demand for drawn art, and the 1990 introduction of Adobe Photoshop substituted computer manipulations for what artists had previously accomplished by hand. At the height of his long career, Lesser had turned out cover illustrations for books by John D. MacDonald, Frank Kane, Carter Brown, Richard S. Prather, and many others. As demand for such works fell off, Lesser—then in his 50s—painted and sold what have been called “visual sagas of the Old West and Civil War.” In the years since, says his Web site, Lesser’s work “has graced the covers of the most prestigious Civil War publications and has been exhibited at the Gettysburg National Park Museum and the National Civil War Museum,” both of which are located in Pennsylvania. In addition, he has painted action scenes focusing on polo horses and their riders, historical still-lifes, distinctive celebrity images, and “romantic fantasy” works.

Book and magazine illustration saw its heyday from about the 1930s through the 1970s. After that, publishers started cutting back on the expense of commissioned paintings. Cheaper photography encroached on demand for drawn art, and the 1990 introduction of Adobe Photoshop substituted computer manipulations for what artists had previously accomplished by hand. At the height of his long career, Lesser had turned out cover illustrations for books by John D. MacDonald, Frank Kane, Carter Brown, Richard S. Prather, and many others. As demand for such works fell off, Lesser—then in his 50s—painted and sold what have been called “visual sagas of the Old West and Civil War.” In the years since, says his Web site, Lesser’s work “has graced the covers of the most prestigious Civil War publications and has been exhibited at the Gettysburg National Park Museum and the National Civil War Museum,” both of which are located in Pennsylvania. In addition, he has painted action scenes focusing on polo horses and their riders, historical still-lifes, distinctive celebrity images, and “romantic fantasy” works.

Lesser currently lives on New York’s Long Island, where I reached him via e-mail. He was kind enough to answer my myriad questions about his life and career, and to separate cover paintings he’s actually done from others that have been mislabeled (on the Web) as demonstrating his talents. During our interview, we talked about his education as an artist, his early work for “big-time illustration agencies,” his “sexy girly covers” for paperback crime fiction, his movie-poster endeavors, his preferred models, and his continuing labors on behalf of book publishers and movie-production companies. Ron Lesser doesn’t seem remotely inclined toward giving up his artistic occupations at any time soon.

J. Kingston Pierce: How did you develop your interest in art? Were there people in your family or among your friends who influenced you to become an artist?

RL: I loved comic-book drawings when I was very young, around 9 to 12 years old. Especially the best-drawn comics. I loved Alex Raymond—he was the cartoonist best known for Flash Gordon. I loved Milton Caniff—he made Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon. I liked Al Capp, who made Li’l Abner and Daisy Mae. Also Superman, Batman, etc. I still love Caniff and Alex Raymond, both outstanding artists.

RL: I loved comic-book drawings when I was very young, around 9 to 12 years old. Especially the best-drawn comics. I loved Alex Raymond—he was the cartoonist best known for Flash Gordon. I loved Milton Caniff—he made Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon. I liked Al Capp, who made Li’l Abner and Daisy Mae. Also Superman, Batman, etc. I still love Caniff and Alex Raymond, both outstanding artists.

JKP: At what point in your boyhood did you start to draw? And what were you drawing then—your own comic books, perhaps?

RL: I don't remember when I started to draw, probably when I was around 12. Probably comics.

JKP: Biographical notes available online say that you graduated from New York City’s High School of Music & Art. In what year did you graduate from there?

RL: I believe it was 1958.

JKP: After leaving high school, you studied at the Pratt Institute of Art in New York. During what years were you a student there?

RL: I went to Pratt in 1958, but stayed less than a semester.

JKP: You dropped out of Pratt early? Why?

RL: I realized that my goal was to be an illustrator and I would never achieve my goal at Pratt. The illustration program was for amateurs. I went to the dean and told him I was leaving. He tried to talk me out of leaving, but I would not be persuaded. I would never reach my potential if I stayed at Pratt. For me, it was a waste of time.

JKP: So, I am given to understand that shortly after leaving Pratt, you enrolled in the Art Students League of New York (ASL). Was it an eye-opening or intimidating experience to be among students as concentrated as you were on artistic expression?

RL: At the League I studied with the great teacher of drawing, painting and illustration, Frank J. Reilly. I certainly was intimidated at first. The best students were outstanding. And these were students. I realized that if I was to succeed I had a lot to learn. I was talented, but not close to competing as a professional.

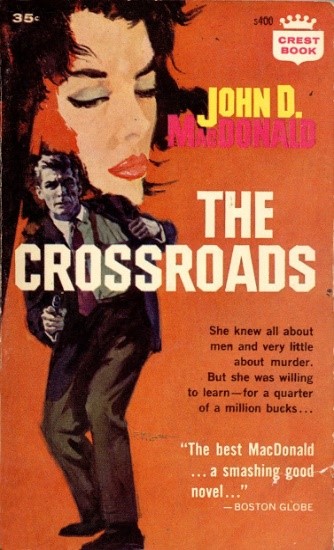

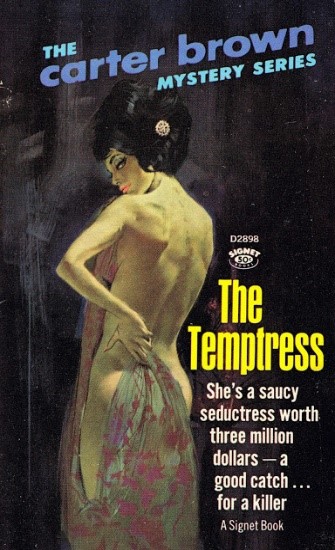

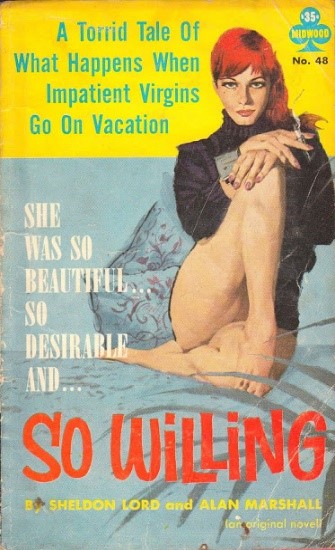

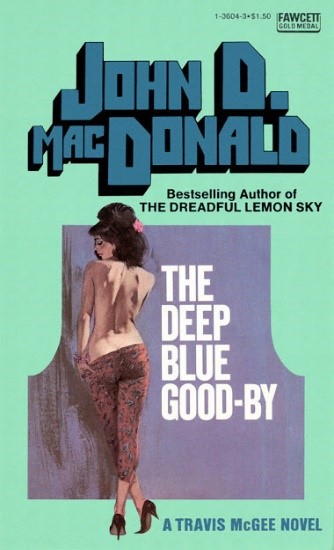

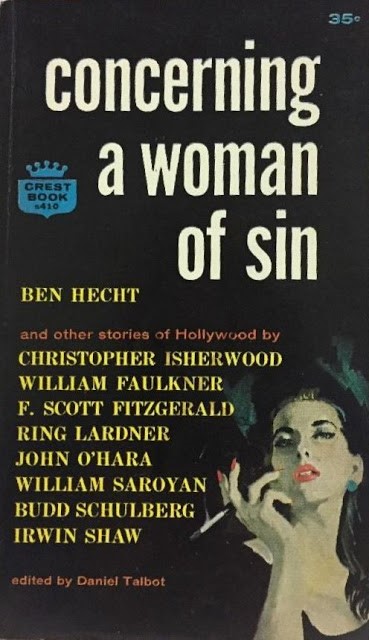

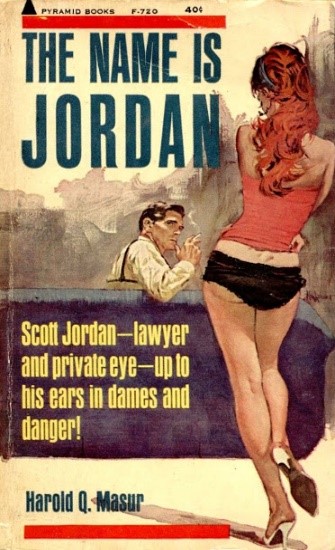

Ron Lesser recruited his wife, Claudia, as a model in many of his paperback covers. Above are six of the artist’s favorite fronts on which she appears: The Crossroads, by John D. MacDonald (Crest, 1960); The Temptress, by Carter Brown (Signet, 1966—see Lesser’s original artwork here); So Willing, by Sheldon Lord and Alan Marshal (Midwood, 1960); The Deep Blue Good-by, by John D. MacDonald (Fawcett Gold Medal, 1981); Concerning a Woman of Sin, edited by Daniel Talbot (1960); and The Name Is Jordan, by Harold Q. Masur (Pyramid, 1962). Claudia also modeled for Curtains for a Lover, shown atop this post.

JKP: I’ve read an abundance of favorable comments about Reilly’s teaching style and his ability to inspire students. But how did he come across to you? And was Reilly especially influential in your own artistic development? What classes did you have with Reilly?

RL: I only studied with Reilly at the League, no other teacher. The ASL is not like a “normal” school or college. There are no grades, no graduation. You enroll with a specific teacher, not with a series of teachers and classes.

Reilly was much more than influential. I would never have learned to draw and paint if I had not studied with Reilly. A Reilly class was like going back in time to what is now considered the “Golden Age of Illustration.” He taught me the tradition and techniques of the French Fine Arts Academy of the 19th and 20th centuries. Reilly was a link to Jean-Léon Gérôme, Paul Delaroche, Jules-Joseph Lefebvre [as well as to] American artists George Bridgman, Dean Cornwell, and Howard Pyle. I do not believe anything like that exists today. I also attended his classes at Woodstock [New York] in the summer; those were for landscape. I really do not recall exactly how I came to enroll with Reilly. I am sure I must have heard about him at Pratt.

JKP: Were you also studying art beyond the classroom, too?

RL: I went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art many times to look at the amazing paintings there. Since the Met is a public museum, all paintings are open to the public, but only a portion are on exhibit. [Others can be retrieved by request.] I remember I gave whoever was in charge of this sort of thing a list of paintings I wanted to see. Several months later I received a notice to appear at a date certain at the museum. I went down into the bowels of the Met with the slip I was given, along with a guard. A huge door was opened. The guard pulled out the paintings I requested to study. It was like a Norman Rockwell cover for The Saturday Evening Post: The guard sat in a chair with a newspaper looking bored and thinking what kind of nuisance and fool I was. Hundreds of paintings in the museum, and I was making all this work for him. All the while I was getting as close as I could to these marvelous paintings to study their craft.

JKP: How long did you wind up studying with Reilly at the ASL?

RL: Four years. The last year, I was a monitor—like a student teacher.

JKP: So in what year did you graduate from the Art Students League?

RL: One does not “graduate” from the League. I went back to visit on occasion. Reilly left the League soon after I left his class, to set up his own school. That was a mistake. He needed the League. He died shortly after he left.

JKP: What did you do for work in those first years after leaving the ASL? Did you move into commercial art/illustration, or did you take another path? Were you working freelance or for a company?

RL: I was making paperback covers while I was at the ASL. I was with the Fredman-Chaite Studios for a short time. There were several big-time illustration agencies that partnered with illustrators through the late ’30s and ’50s. The agencies took their cut from advertising jobs. [But] the illustrators were not required to give the agency a cut from editorial work, magazines, paperback covers, etc. The idea being, from the agencies’ point of view, [that] magazine commissions were good for promotion, [helping] to acquire the advertising jobs which paid a lot more. However, photography was rapidly moving into the space that the illustrator had had to himself for years. So by 1965 the large illustration agencies, like Fredman-Chaite and [Charles E.] Cooper Studios, went out of business. When I was starting I made Western and sexy crime babes to be used for paperback covers on spec, and sold them. Since Westerns were for the most part generic, as were the sexy girls, they were not hard to fit for a cover.

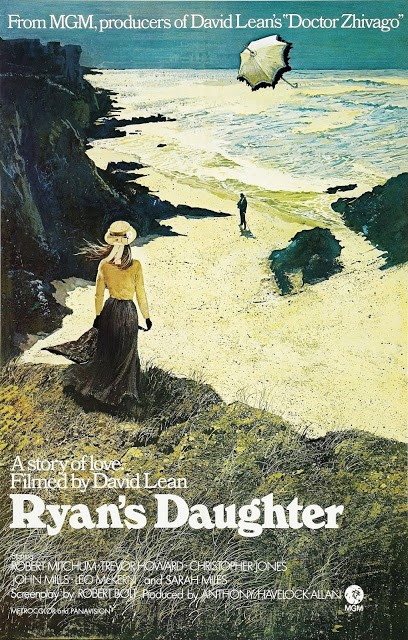

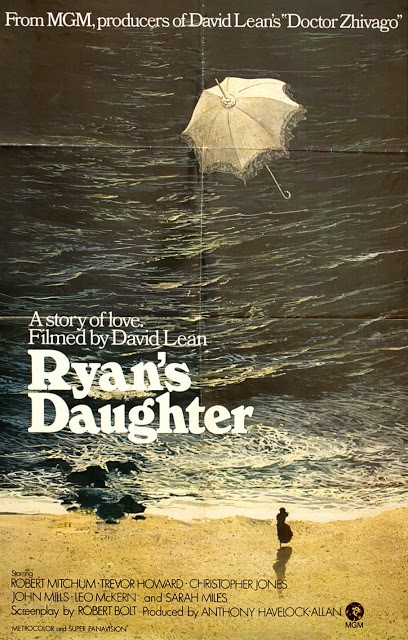

Ron Lesser produced two full-color promotional posters for the 1970 film Ryan’s Daughter. “My wife posed for all three, of course,” he says. “It was not common for one artist to make three paintings for the same movie. The [James] Bond movies were an exception.” Lesser also created a third, black-and-white poster, which was used in newspapers and can be seen here.

JKP: How did you start selling movie-poster art to the Hollywood studios? Were you mostly doing that on spec, too? And what was your first movie poster sale?

RL: Movie art was never on spec, except on this one occasion for [Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s 1970 romantic drama] Ryan’s Daughter. That was my first movie painting, for Ryan’s Daughter. I came onto that opportunity very late. While at my agents’ office, I noticed some artists were making sketches for the movie. I asked what that was about. I was told they were making sketches for Ryan’s Daughter, a big-time movie directed by David Lean. I wanted to get in on that. Remember, I was a novice at that time—no résumé at all. My agents laughed at the idea [of me winning the job]. I was told that every illustrator with a reputation in New York was working on this. There were meetings that they attended with the client. No way could I expect to get this opportunity. But I would not be deterred. Somehow, I was given a fact sheet and acquired some movie stills. I made two paintings. They were submitted to MGM … and they loved them both. I won the contest!

JKP: How many film posters have you painted over the years?

RL: Probably over 100, if you include ads for television.

JKP: I’ve heard that your favorite from among those posters was the one you did for the 1973 film High Plains Drifter.

RL: Only because it became an iconic poster and led to several Clint Eastwood movie commissions. Other than that it is not my favorite.

JKP: Which leads me to ask, of course, which was your favorite?

RL: Probably both paintings I made for Ryan’s Daughter. Claudia was my model for both of these paintings.

JKP: Were you actually employing her for that work?

RL: She was not employed. I did not pay Claudia. She did not like to pose, although she was a very good model. As soon as I could afford to pay models, I stopped using her most of the time, although I could get her to pose when I wanted to. One time I lost all of a [model pose] shooting I took in New York City, and I recovered by shooting Claudia. I’d left the photography on the subway.

JKP: Do you continue to take on movie-poster assignments?

RL: Of course, but there are very few opportunities for movie art today. I recently did the art for Atomic Blonde with Charlize Theron. [You can see his work here.] That was a pleasure painting the beautiful Charlize Theron. I have always loved to paint gorgeous women. Beautiful women are the most fun for me to paint.

JKP: Let’s move on to the subject of your book covers. Do you remember which of those was the first one you worked on?

RL: Reilly had several contests during the year [at the ASL]. I came in second in one contest. It was [for] a Western scene and was used by the client, Berkley Books, [on a 1960 William O. Turner novel] titled War Country. I think that was the first time I was published.

RL: Reilly had several contests during the year [at the ASL]. I came in second in one contest. It was [for] a Western scene and was used by the client, Berkley Books, [on a 1960 William O. Turner novel] titled War Country. I think that was the first time I was published.

JKP: Approximately how many paperback book covers have you painted over the years?

RL: I made several thousand covers. Too many to list a favorite. I was awarded several gold medals and best-of-show certificates from The Society of Illustrators. [I also won] Best Movie Art from the Art Directors Club of New York. That painting was for [the 1974 science fiction/fantasy film] Zardoz, starring Sean Connery.

JKP: I’m surprised to say I don’t know the answer to this: Have you painted covers for hardback books as well as paperbacks?

RL: Yes, many covers.

JKP: Which paperback publishers kept you the busiest?

RL: Dell, Fawcett/Gold Medal, New American Library/Signet, Harlequin, Avon—really, all of them.

JKP: How have you usually gone about creating book-cover art?

RL: I am assuming you are talking about a commission. During my major illustration career, the client paid for all expenses. I would photograph the job using models. Often I would make sketches after the photography was done. If additional photography was needed, I usually could piggyback the additional photography [on] the next session. This was not a problem, since I was always booked for several months, so there was always another job.

JKP: And can I assume you didn’t actually read the books for which you were creating art, but that publishers gave you suggestions of what they’d like to see in your finished work?

RL: That would depend on the type of cover. You are right, I never read the books. The “girly books” rarely fit the book cover [art]. I had two different paperback careers. For the first nine to 10 years, I made Western and girly covers. I am best-known for my “sexy girly covers.” However, for the years I was very successful, I made mass-market covers with famous authors. That was for about 15 years … For these covers, the art did fit the story.

JKP: I am most familiar with those sexy girly covers. When you say you later “made mass-market covers with famous authors,” to which authors do you refer? Two or three names will suffice.

RL: Jack Higgins, Helen Hooven Santmyer, Peter Albano.

JKP: Have you had some favorite models for your paperback work? It looks as if the extremely popular Steve Holland might have appeared on some of your Westerns—is that correct?

RL: I used Steve Holland a lot; however, he was used so much by so many artists, that some publishing companies asked me not to use him. The only other time I can think of that a company asked me to use a model less, because I used her so much, was Harlequin Books. The model's name is Jane Minion. I hope she will not have an issue with my naming her. She was the best female model I ever used.

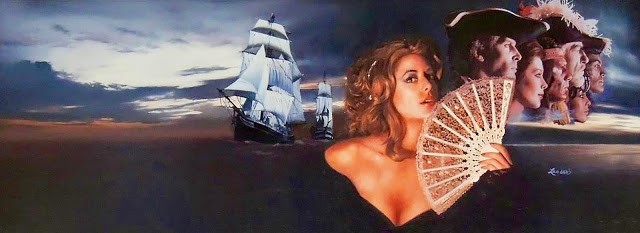

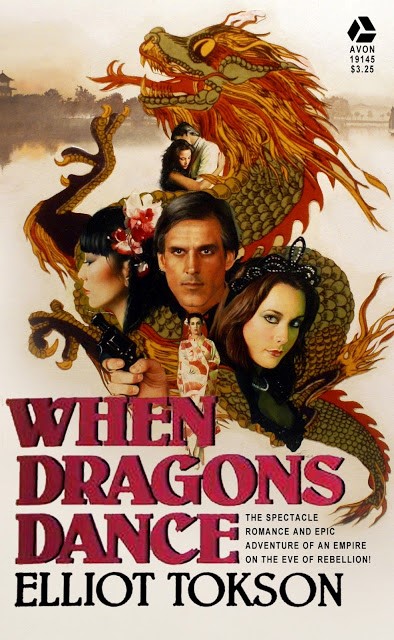

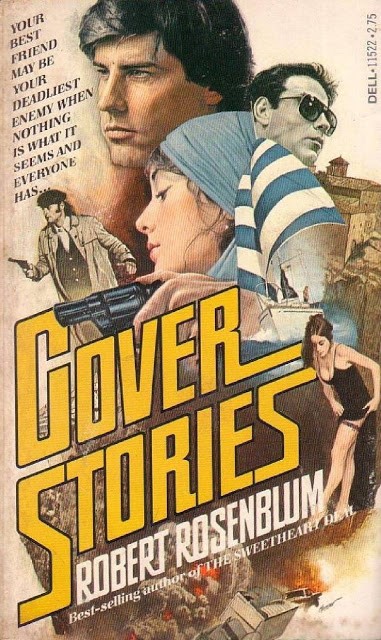

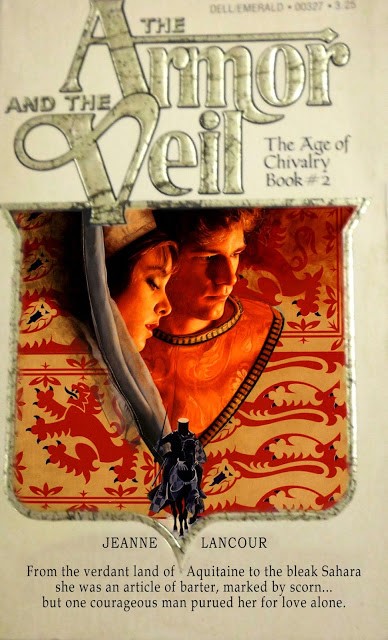

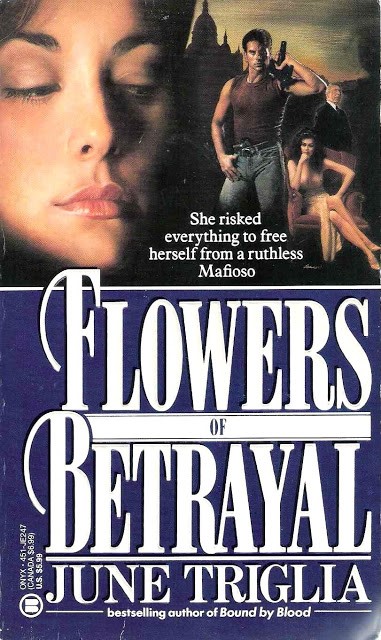

Here’s a selection of Ron Lesser cover art featuring model Jane Minion. Above: The full, original painting for Goodly Heritage, by Beverly McGlamry (Ballantine, 1986—published cover here). Below: When Dragons Dance, by Elliot Tokson (Avon, 1982); Cover Stories, by Robert Rosenblum (Dell, 1980—original artwork here); The Armor and the Veil, by Jeanne Lancour (Dell Emerald, 1982); and Flowers of Betrayal, by June Triglia (Onyx, 1981—original artwork here). Click on these images for enlargements.

JKP: Did you paint your book covers in oil, or in some other medium? And what size canvases did you prefer for such assignments?

RL: Early in my career, I used water-based designers’ colors with casein white. Most of my career I used oil. Size varied.

JKP: You’re probably best known for having painted the fronts for crime and Western novels. But have you also created covers for many romance novels, or for works of science fiction?

RL: I made several hundred covers for Harlequin [in the 1980s]. I was given a two-year contract from Harlequin. I was required to make at least one cover a month. That was to leave me time for other publishing covers and different subjects. However, Harlequin gave me so much work for the length of the contract, that there was no time available for anything else. I refused to renew, because I did not want to do another romance cover. I still continued to paint for Harlequin, but not exclusive. No science fiction.

JKP: You created a large quantity of book covers during the 1960s and ’70s. Not long after that, though, publishers started to substitute photographs for drawn or painted artwork. What was that transition like? Did it seem sudden and frightening, or was there ample forewarning? And was the reason for the switch-over based solely on money (photos being cheaper), or were there other considerations in play back then? I’m interested to know your perspective.

RL: The transition from art to photography for paperback covers did not happen until 1992, for the most part. During the ’60s through the ’80s, there was not a problem regarding photography and Photoshop. However, since 1985 there has been very little movie art done. The movie posters were all done in California using movie stills. Advertising using illustrators had been long gone, back to the early ’60s.

Yes, [the transition] was sudden. Overnight, many excellent illustrators were out of business. The publishing companies discovered Photoshop. They could get a cover made for $1,000 instead of $3,500 to $5,500. That was the biggest reason. I switched to galleries, painting Western art.

JKP: In recent years, you’ve begun painting paperback covers again, this time for Hard Case Crime. Did Charles Ardai have to do much persuading to get you back into the business, or were you ready to tackle such art again? And can we expect to see more of your work on Hard Case releases in the near future?

RL: I loved painting [Ardai’s] covers. As to my doing more for Hard Case, you’ll need to ask Charles. [Editor’s note: Ardai tells me, “We don’t currently have any covers assigned to [Lesser], but I was chatting with his representative just the other day about the possibility of getting him involved with our comic-book line at some point, so who knows? We don’t publish nearly as many new books per year now as we did a decade ago, so we don’t have as many covers to assign, but it would certainly be fun to work with Ron again at some point.”]

JKP: You’ve firmly established your artistic reputation as a realist. What made you inclined toward fine realism, while many others preferred more abstract expression?

RL: I do not recognize abstract or any other -ism as a legitimate form of art, except fine realism.

JKP: At what point did you become interested in Old West still-life paintings, as opposed to Western book-cover art?

RL: I have a large collection of western material, Indian weapons and material. About three years ago I made this series.

JKP: How did a New Yorker become enamored of Old West subjects? Can we credit your work on Western novel covers for that?

RL: I loved making Western paintings. Not as much as painting sexy babes, but after that. Jimmy Bama and Frank McCarthy were New York artists. Bama was also a Reilly student.

JKP: Finally, let me ask what projects you’re working on now.

RL: I started this new series of paintings about seven weeks ago. It is market- and sales-driven. The series is the “Timeless Beauty of European Medieval Village Streets.” I plan to make these paintings as long as they sell. I have never made paintings for vanity reasons. Since I left Reilly I have always been a commercial artist.

Two pieces from Lesser’s new “Timeless Beauty of European Medieval Village Streets” series. Above: “Beautiful Ancient Village of Provence, France.” Below: “Ancient Village Street in Southeastern France.” More can be found here.

To see more of Ron Lesser’s fine-art work, check out the following Web sites: Going to the Sun Gallery, Whitefish, Montana; West Lives On Gallery, Jackson Hole, Wyoming; and River Road Gallery, Wilton, Connecticut.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 7:40 AM

Editor, The Rap Sheet

Editor, Killer Covers

Friday, June 22, 2018

Part of a month-long celebration of Ron Lesser’s artistic legacy.

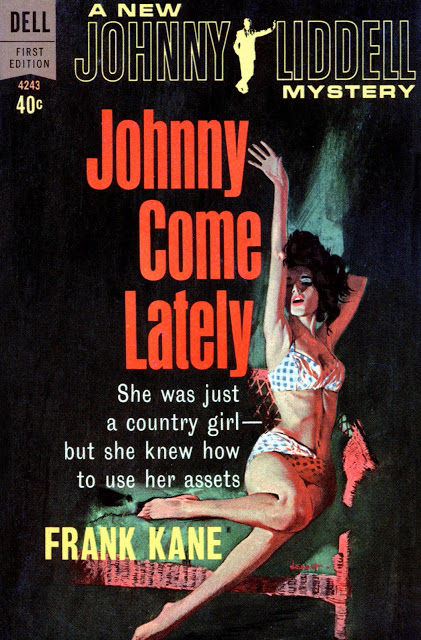

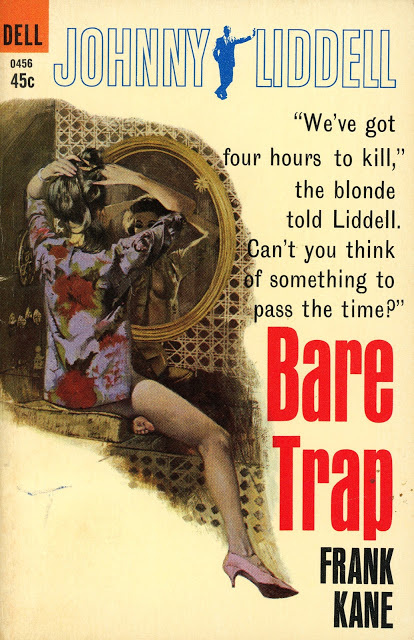

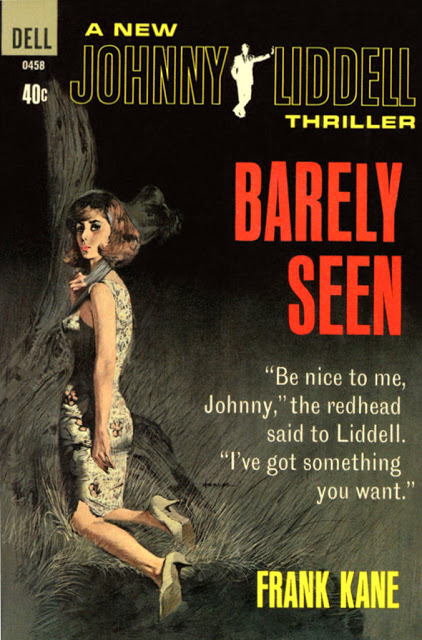

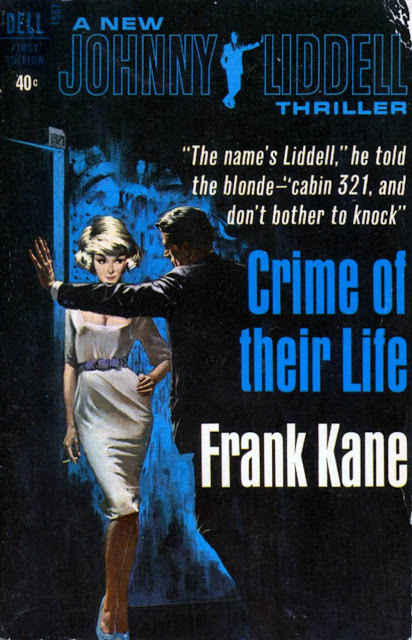

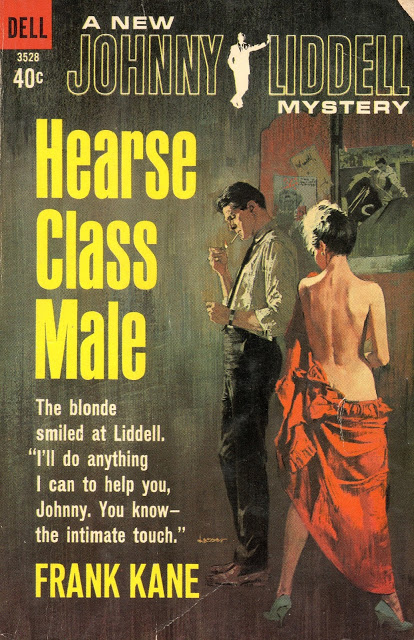

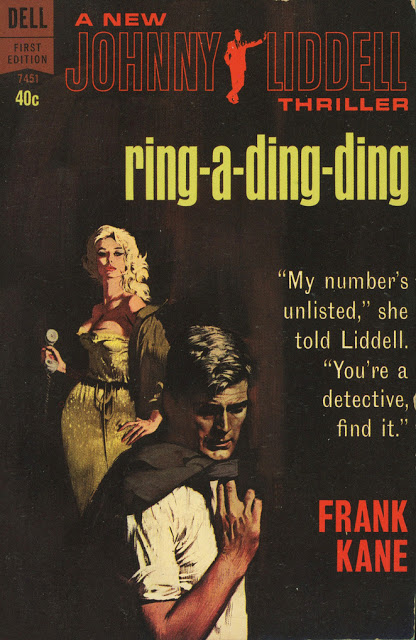

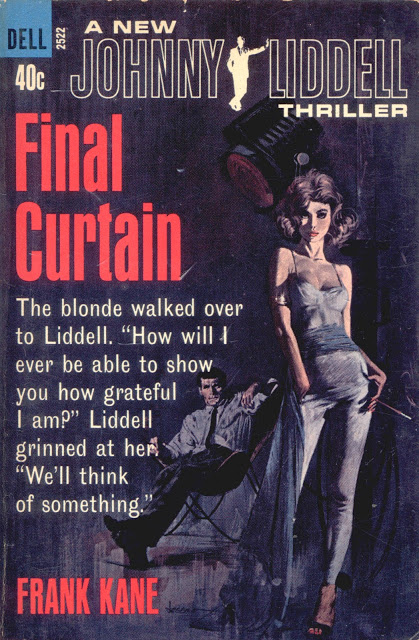

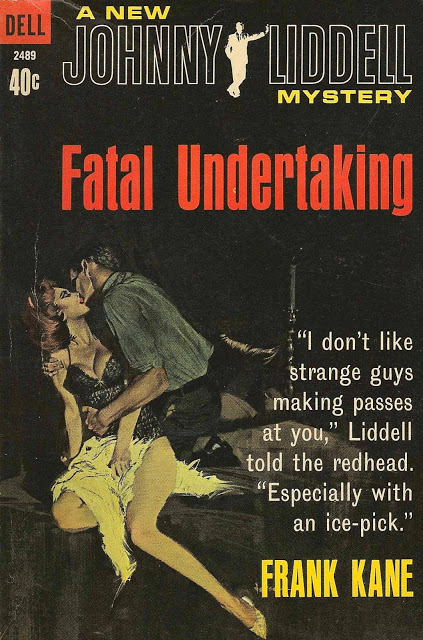

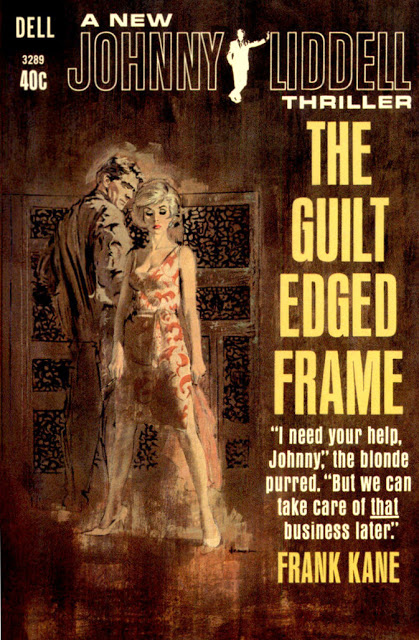

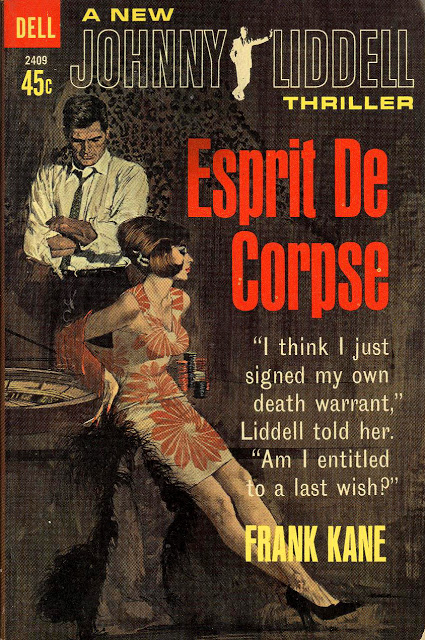

During the early to mid-1960s, publisher Dell assigned two American painters to create compelling cover artwork for Frank Kane’s then best-selling mystery series starring New York City private investigator Johnny Liddell. You can see Harry Bennett’s paperback fronts in this Killer Covers piece published a few months ago. Today we look—above and below—at Ron Lesser’s illustrations for 10 mostly different Liddell yarns.

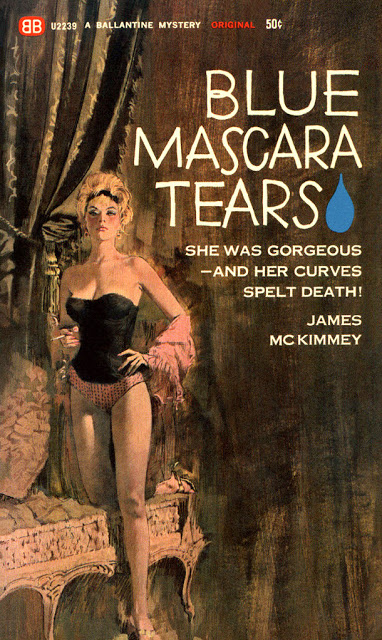

Lesser’s wife of four decades, Claudia, posed for the covers of both Bare Trap (1965) and Hearse Class Male (1963). The artist adds that “the models for Fatal Undertaking were Lisa Karen”—previously seen on Blue Mascara Tears—“and Steve Holland. Lisa Karen also posed for Johnny Come Lately.”

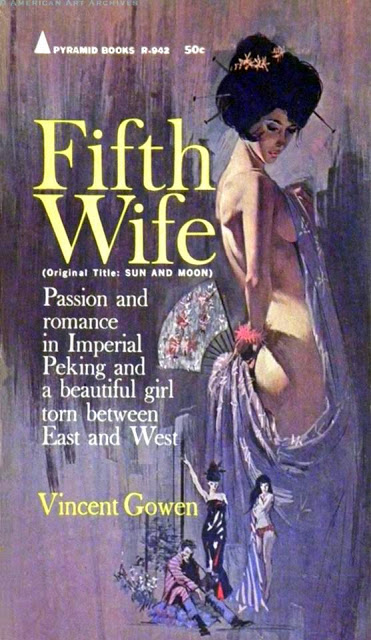

Fifth Wife, by Vincent Gowen (Pyramid, 1963; originally published in 1927 as Sun and Moon). It wasn’t until yesterday that I realized Father Gowen (1893-1984) was for many years the vicar at an Episcopal church on Bainbridge Island, located just west of Seattle, Washington. However, he had spent part of his youth engaged in missionary work in Asia.

On the matter of his cover art for this paperback edition of Fifth Wife, Ron Lesser explains he once again recruited his own spouse, Claudia, as his model. The fact that Claudia has featured on so many of the novel fronts included in this Killer Covers series (see here, here, here, and here) raises doubts about Lesser’s early statement that “she did not like to pose” for his paintings. But her reign as the artist’s muse seems, at least, to have had a short run; he says that “After the late ’70s I stopped using Claudia.”

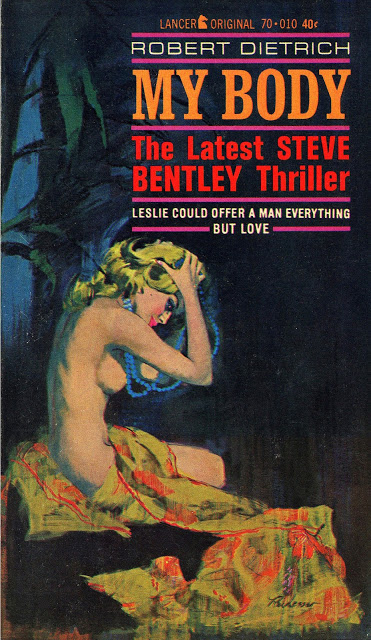

My Body, by “Robert Dietrich,” aka E. Howard Hunt (Lancer, 1973). This was the ninth entry in future Watergate conspirator Hunt’s series of thrillers starring Washington, D.C.-based CPA-cum-private eye Steve Bentley.

The Lesser Look: The End Is Near!

Today brings an end to Killer Covers’ celebration of Ron Lesser’s artistic legacy. Over the course of more than three dozen posts—four of which are still to come—this blog will have turned the spotlight on 60 of his paperback book fronts, as well as a variety of his other paintings, sketches, and movie posters. Despite such coverage, there remain many more Lesser creations we haven’t mentioned, but hope to address at a point not too far in the future.

My special thanks goes to Lesser himself, who—after mild initial hesitation and concerns—patiently answered all of my myriad questions about his life, career, and individual illustrations. I hope that someday his elegant artistry will receive the sort of book-length attention that has already been lavished on paperback-cover artists such as Robert McGinnis, Robert Maguire, and James Avati.

I also extend my gratitude to Charles Ardai, the editor of New York City-based book publisher Hard Case Crime, who encouraged me to contact the usually interview-averse Lesser, and even supplied me with his e-mail address to make that possible.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this series over the last five weeks. I don’t often get the chance to dig into a subject as frequently or as deeply as I have Ron Lesser’s work. With any luck, my efforts here will teach readers to recognize and appreciate this artist’s abundant talents—and, perhaps, encourage them to pick up one of the books he’s illustrated over the last six decades. My own collection of Lesser’s covers has lots of room to grow.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 4:18 AM

Thursday, June 21, 2018

The Lesser Look: Welcome to Summer!

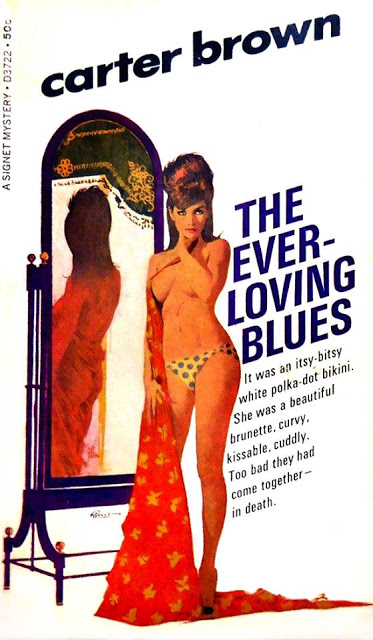

The Ever-Loving Blues (previously published as Death of a Doll), by “Carter Brown,” otherwise known as Alan Geoffrey Yates (Signet, 1969). This is one of at least 30 books starring demonstrably rugged New York City private eye Danny Boyd.

The Lesser Look: But Wait, There’s More

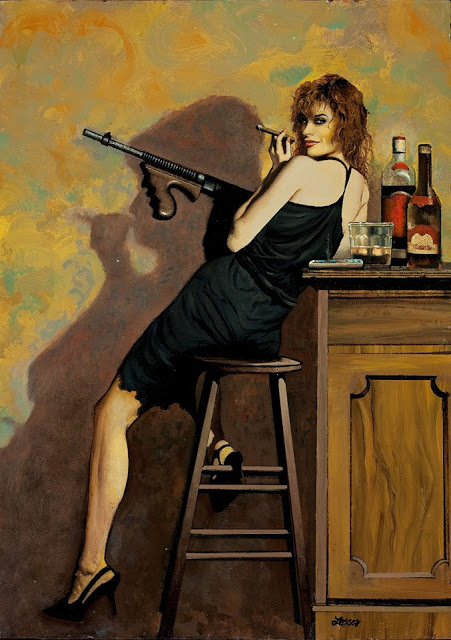

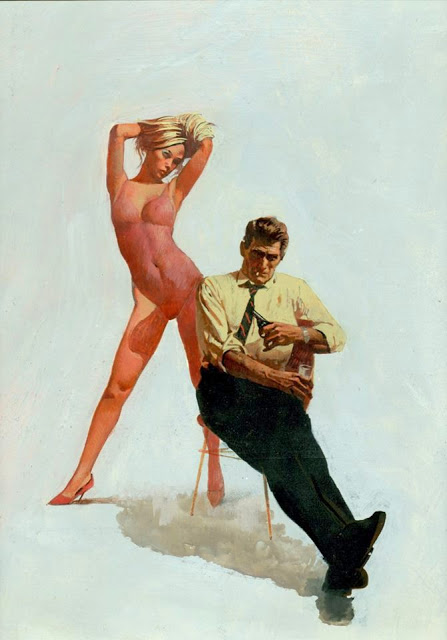

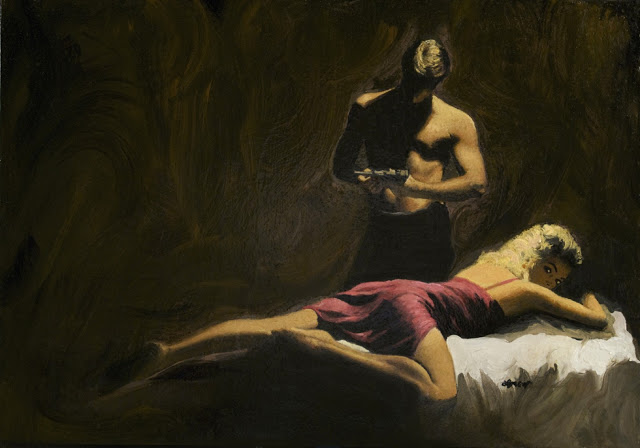

(Above) According to Lesser, this painting was featured in a “Cold Case Detective” calendar he created some years ago.

In addition to the many finished, Ron Lesser-illustrated book covers packed into my computer photo files, there’s also a scattering of paintings he intended for other uses, preliminary body sketches, and original images later cropped or overlaid with type by various paperback book publishers. As Killer Covers’ tribute to this American artist winds down, I want to showcase at least some of those works. I asked Lesser, via e-mail, to comment on the 16 paintings featured above and below, and have based my captions on his remarks.

“For most of my models,” Ron Lesser tells me, “I went through a model agency. Either Ford or Wilhelmina Models. There were several other New York agencies as well. Only models who did illustration photography were available to artists. The price for a model for illustration photography in the 1960s and ’70s was about $100 an hour. In the late ’70s that price went to $150 an hour. In the ’80s the artist paid $200 an hour. The client paid all of the expenses—photographer, model, and print costs.” Referring to two of his favorite cover models, Lesser says: “Steve Holland, who was never with an agency, kept his price at $100 an hour. Jane Minion had an agency for acting, but not a model agency. So I booked her directly, as I did for Steve. Jane was a dancer in the [1979] Bob Fosse-directed movie All That Jazz.”

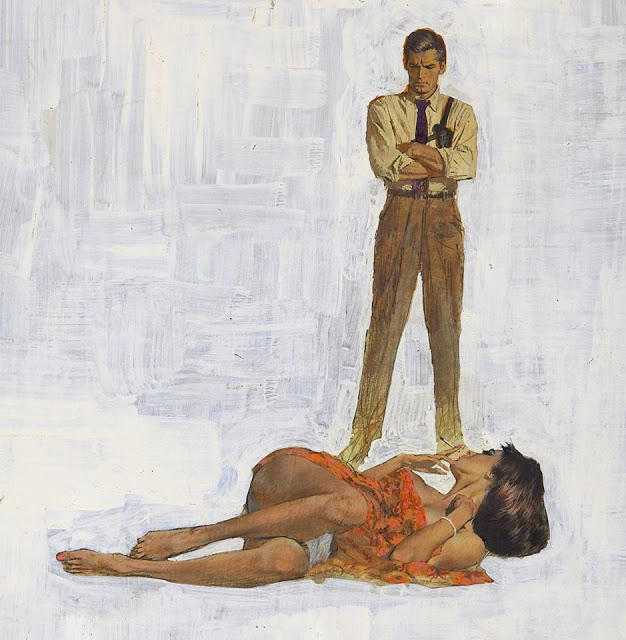

The lovely brunette shown reclining in the image above was Elaine Reynolds, a onetime Playboy model who, Lesser explains, “was in the magazine several times. I used her many times. She was a great model and a very nice lady. I wish her well.” Reynolds can be seen, as well, on the cover of Target for Their Dark Desire.

In case there was any question about this, Lesser notes that “The babe on the chaise longue is Elaine Reynolds.”

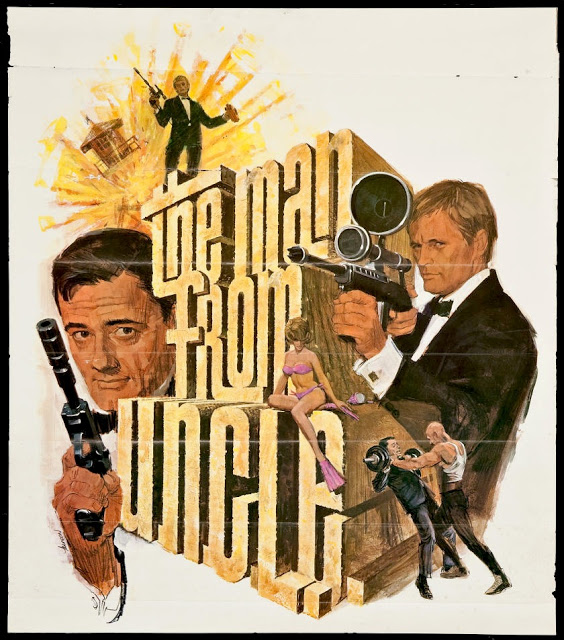

Lesser says this promotional poster for the TV spy series The Man from U.N.C.L.E., starring Robert Vaughn and David McCallum, “would have been done around 1964-65. NBC used several illustrators to make paintings for the coming TV schedule for a few years. Jimmy Bama made several paintings, among other artists. I also did the art for The Dean Martin Show … It was cool to see my paintings on my television, advertising the coming schedule.”

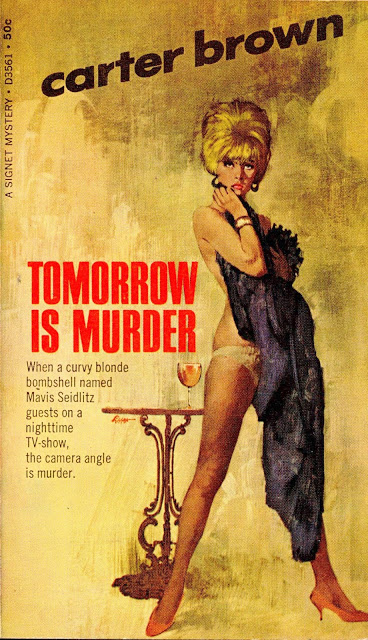

This painting, which Lesser says “was done several years ago for a sale,” bears a striking resemblance to his cover illustration for Carter Brown’s Tomorrow Is Murder

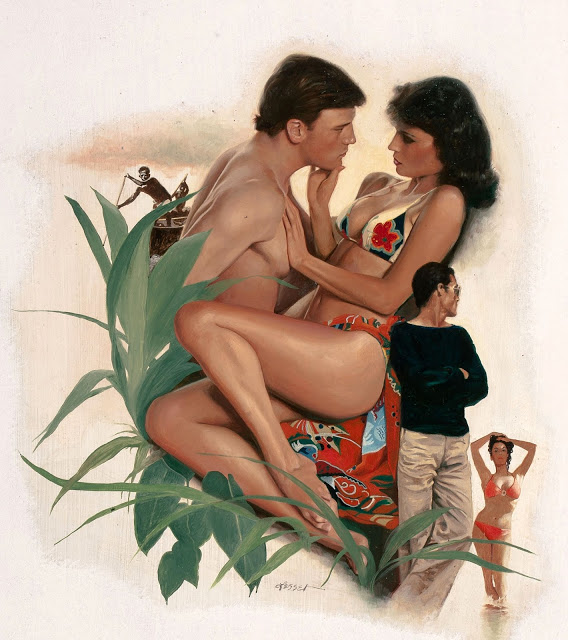

Lesser remembers he wasn’t particularly impressed with the male model he employed for this painting, and that “the small babe in a bikini” is one of his favorite female subjects, Jane Minion.

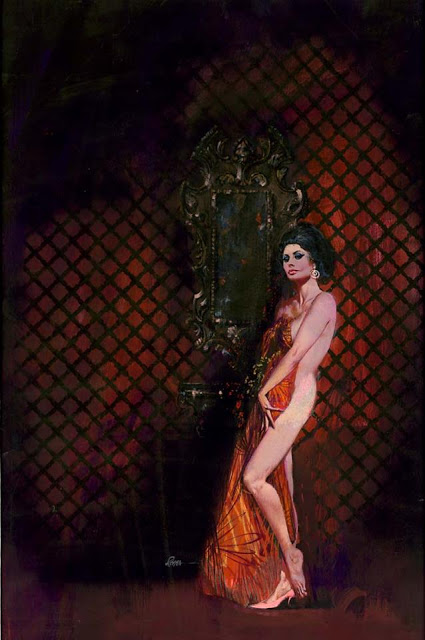

“I never met Sophia Loren …,” Ron Lesser confesses, “[but] I loved to paint her face. Great bones.” He created the image shown above for the 1979 Baronet paperback edition of Forever Sophia: An Intimate Portrait, by Alan Levy. Meanwhile, the distinctly more provocative image of Loren displayed below graced the 1967 Signet edition of Lament for a Lousy Lover, an Al Wheeler/Mavis Seidlitz novel by Carter Brown. Says Lesser: “I plead guilty to placing [Loren’s] head over a different body. In this painting the body belonged to Elaine Reynolds. I did this several times. No one ever seemed to notice.” By the way, Lesser had at least one more opportunity to paint the lovely Loren, for the poster promoting her 1979 film, Firepower.

One other screen queen Lesser has painted more than once is Marilyn Monroe. Of the image shown above, titled “Marilyn in Silk Scarf,” he writes: “A gallery that represented me wanted me to make this painting. I sold the painting to The Illustrated Gallery,” located in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania. To enjoy another of Lesser’s Monroe paintings, click here.

“I have no idea what these drawings were for,” Lesser admits. “Probably preliminary sketches for a book cover.”

The armed man in the painting presented above is the seemingly ubiquitous Steve Holland. Lesser identifies the blonde posing behind him as “a very cute model, Vickie Chesire.”

The title of this historical painting is “Reflection.”

Frederic Brown’s The Wench Is Dead was originally published in 1955. However, Centipede Press brought out a new hardback edition of that novel (plus bonus stories) in 2017, compete with the Ron Lesser wraparound artwork shown above. “The book sold out,” Lesser recalls. His female model here was again Jane Minion. The artist relates his uncomplicated technique for lightening her dark locks in this pose: “If the babe in the story was a blonde, I posed her with a wig. [Minion’s] hair was auburn. I had a cheap blond wig that Jane could make look pretty good. Being of Italian heritage, she was great with hair.”

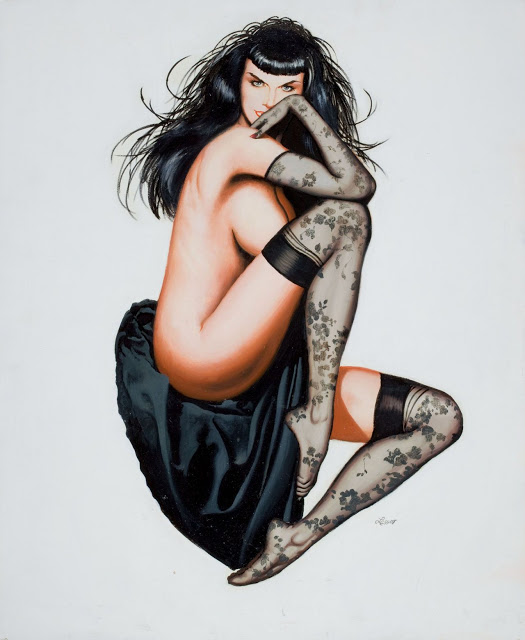

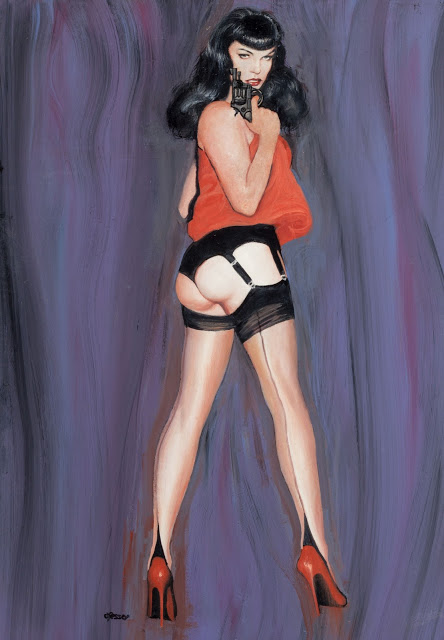

Another famous figure who’s shown up on more than one Lesser canvas in the past is the so-called Queen of Pinups, former Playboy model and fashion icon Bettie Page. As with the second Sophia Loren illustration in this post, the final two paintings here show Page’s head mounted atop curvaceous bodies conceived by Lesser. The image above is called “Too Hot to Touch,” while the painting below carries the title “I’m No Angel.”

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 10:15 AM

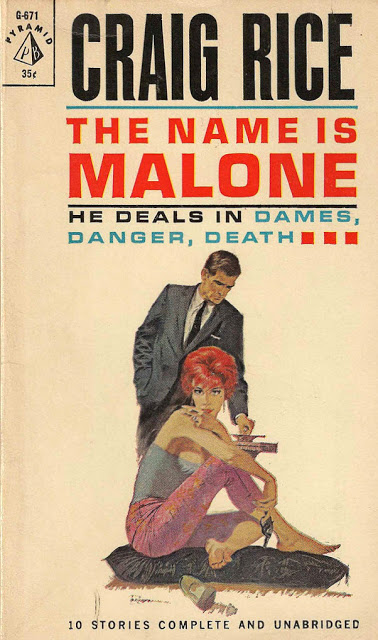

The Lesser Look: “The Name Is Malone”

The Name Is Malone, by Craig Rice (Pyramid, 1961).

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 4:55 AM

Wednesday, June 20, 2018

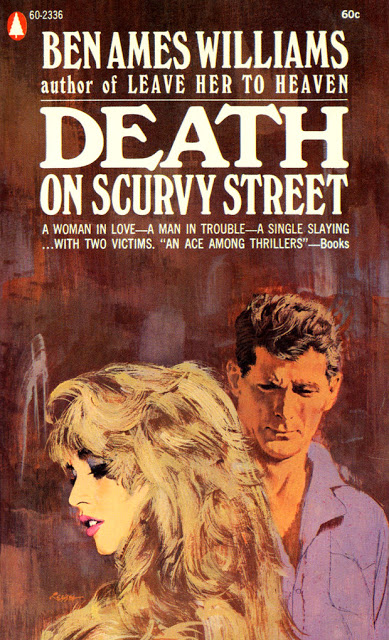

The Lesser Look: “Death on Scurvy Street”

Death on Scurvy Street, by Ben Ames Williams (Popular Library, 1956). This novel was also published as The Bellmer Mystery.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 8:32 AM

Tuesday, June 19, 2018

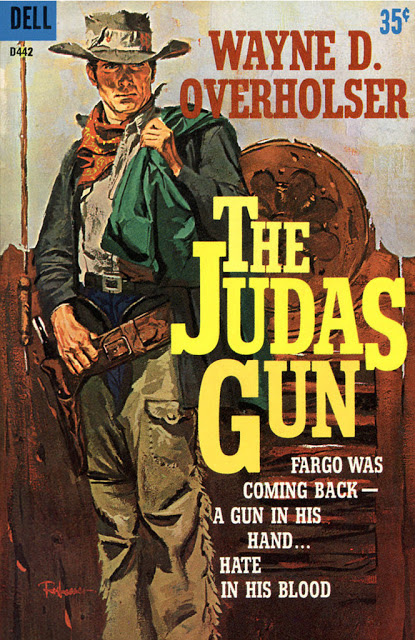

The Lesser Look: “The Judas Gun”

The Judas Gun, by Wayne D. Overholser (Dell, 1961).

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 12:12 PM

Part of a month-long celebration of Ron Lesser’s artistic legacy.

During the course of my original interview with Ron Lesser, this last April, I asked him whether there were any specific artists who had been particularly influential on his work. He quickly responded, “Norman Rockwell.” Shortly thereafter, though, he e-mailed me a list of “other artists that I really love,” noting in his introduction to it that “I will not mention living illustrators for reasons you can assume.” Below is Lesser’s list, with his comments.

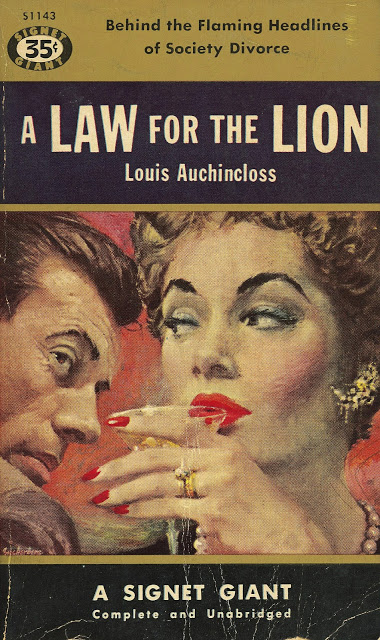

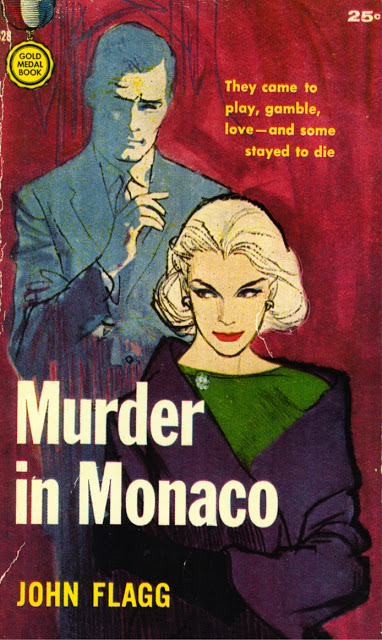

A Law for the Lion, by Louis Auchincloss (Signet, 1954), with cover art by Stanley Zuckerberg; Murder in Monaco, by John Flagg (Gold Medal, 1957), with an illustration by Bob Peak.

Illustrators:

• Stanley Zuckerberg—very underrated. I believe he was the best illustrator/artist making paperback covers during the very “painty” period of the 1940s through the ’60s. Also James Avati [who had a] similar style, but [there was] no one better than Zuckerberg.

• Joe Bowler and Coby Whitmore. I used to look in the large window of the Charles E. Cooper Studio, which was east of the Art Students League, and admire these excellent illustrators.

• Frank McCarthy, who was with Fredman-Chaite Studios, along Bob Peak; and I believe Bernie Fuchs was there as well.

• Before this group there was Dean Cornwell, who was a huge influence on [my teacher] Frank J. Reilly.

• Harold von Schmidt. I used his son for some of my Western paintings, including this one.

• Tom Lovell—an incredible artist, none better.

• N.C. Wyeth, also marvelous.

• Frederic Remington.

19th-century artists:

• Frederic Leighton and Jules Joseph Lefebvre—it was these artists I was studying when I had the [New York Metropolitan Museum of Art] open its vault. I was with Reilly at this time.

• Also William-Adolphe Bouguereau. Maybe among the very best artists of all time.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 7:37 AM

Monday, June 18, 2018

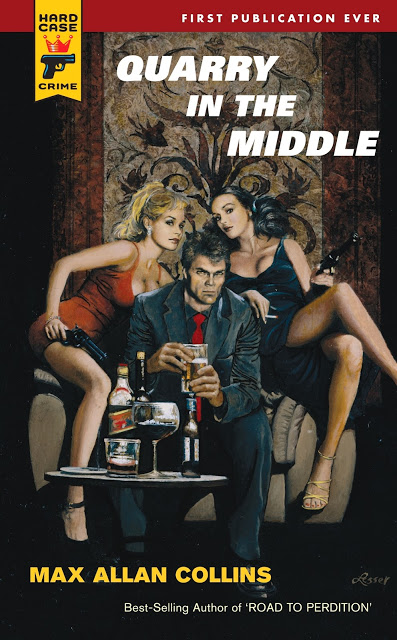

The Lesser Look: “Quarry in the Middle”

Quarry in the Middle, by Max Allan Collins (Hard Case Crime, 2009). This is the eighth entry in Collins’ series featuring a randy, peripatetic hit man known only as Quarry.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 5:23 AM

Sunday, June 17, 2018

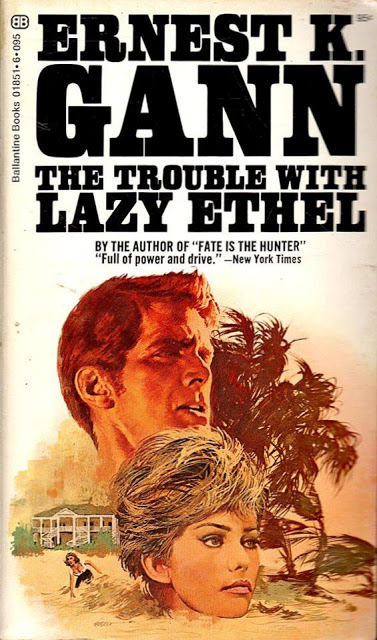

The Lesser Look: “The Trouble with Lazy Ethel”

The Trouble with Lazy Ethel (Ballantine, 1970), by Lincoln, Nebraska-born aviator-turned-author Ernest K. Gann.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 6:06 AM

Saturday, June 16, 2018

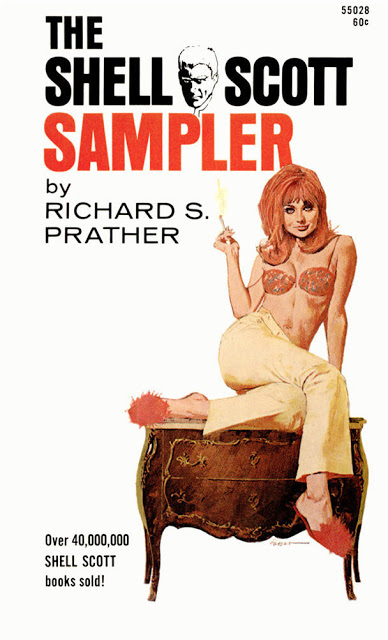

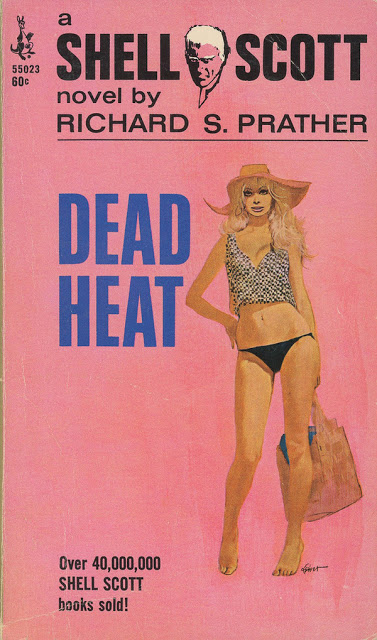

Dead Heat, by Richard S. Prather (Pocket, 1967). Part of Prather’s long-running Shell Scott private-eye series.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 7:51 AM

Friday, June 15, 2018

The Lesser Look: “Tomorrow Is Murder”

Tomorrow Is Murder, by “Carter Brown,” aka Alan Geoffrey Yates (Signet, 1968). This is one of Brown’s dozen novels starring “ravishingly beautiful” but slightly ditzy gumshoe Mavis Seidlitz.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 5:44 AM

Thursday, June 14, 2018

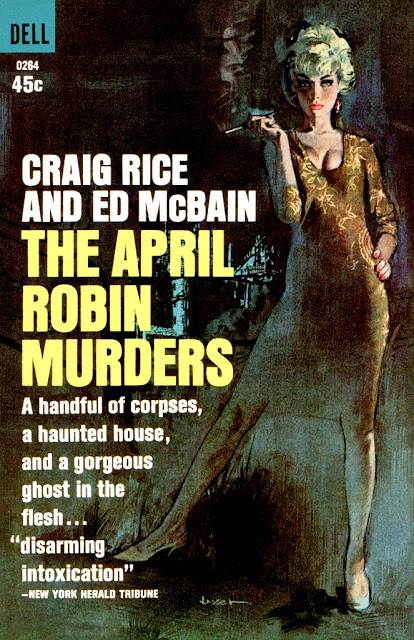

The Lesser Look: “The April Robin Murders”

The April Robin Murders, by Craig Rice and Ed McBain (Dell, 1965). This was Rice’s final novel, left unfinished at the time of her death in 1957, at age 49. The book was ultimately completed by Evan Hunter under his “Ed McBain” alias.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 6:19 AM

Wednesday, June 13, 2018

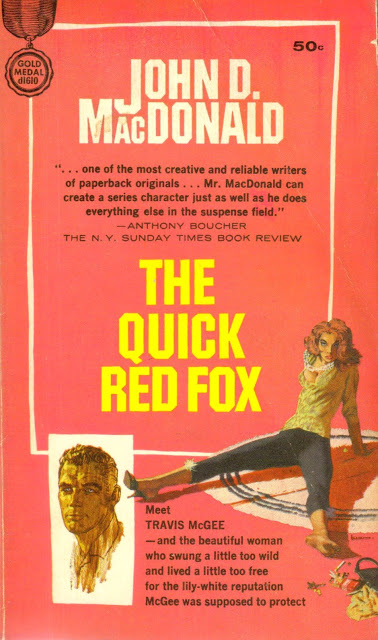

The Lesser Look: “The Quick Red Fox”

The Quick Red Fox, by John D. MacDonald (Fawcett Gold Medal, 1964). This is the fourth entry in MacDonald’s Travis McGee series. The main cover art is by Ron Lesser, but the inset portrait of McGee was done by John McDermott.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 8:01 AM

Tuesday, June 12, 2018

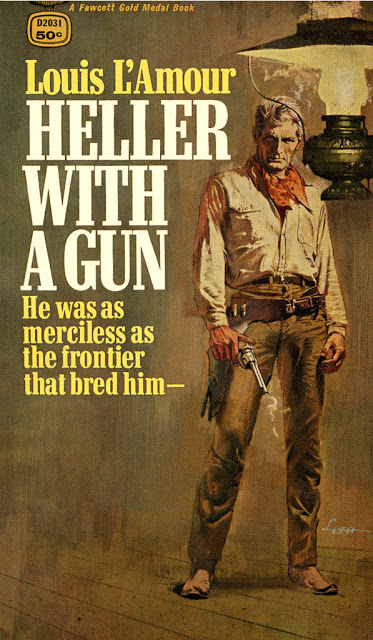

The Lesser Look: “Heller with a Gun”

Heller with a Gun, by Louis L’Amour (Fawcett Gold Medal, 1969). This novel served as the basis for Heller in Pink Tights, a 1960 Western film starring Sophia Loren and Anthony Quinn.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 4:38 AM

Monday, June 11, 2018

The Lesser Look: “Target for Their Dark Desire”

Target for Their Dark Desire, by “Carter Brown,” aka Alan Geoffrey Yates (Signet, 1966). This is one of Brown’s many novels starring Al Wheeler, a sheriff’s homicide investigator who operates in fictional Pine County, California, near Los Angeles.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 6:22 AM

Sunday, June 10, 2018

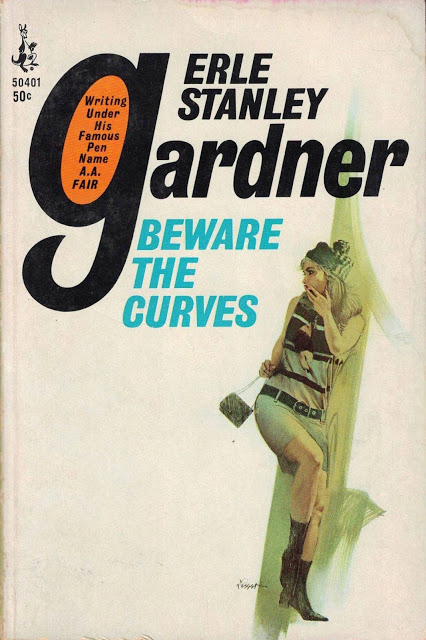

The Lesser Look: “Beware the Curves”

Beware the Curves, by “A.A. Fair,” aka Erle Stanley Gardner (Pocket, 1966). This is the 15th book in Gardner’s series featuring mismatched Los Angeles private eyes Bertha Cool and Donald Lam. Ron Lesser created the cover for at least one other Cool and Lam novel, Bats Fly at Dusk.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 5:40 AM

Saturday, June 9, 2018

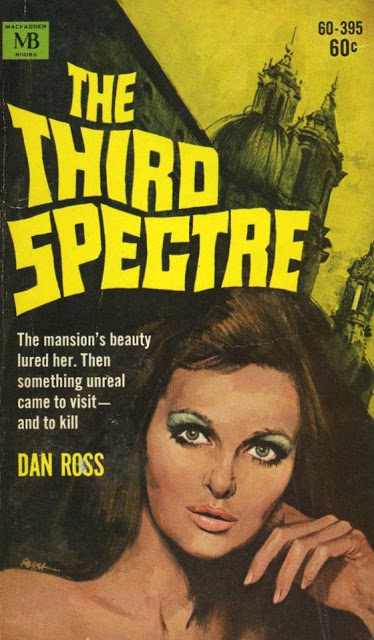

The Lesser Look: “The Third Spectre”

The Third Spectre, by “Dan Ross,” one of several pseudonyms used by Canadian writer W.E.D. Ross (Macfadden, 1967).

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 3:17 AM

Friday, June 8, 2018

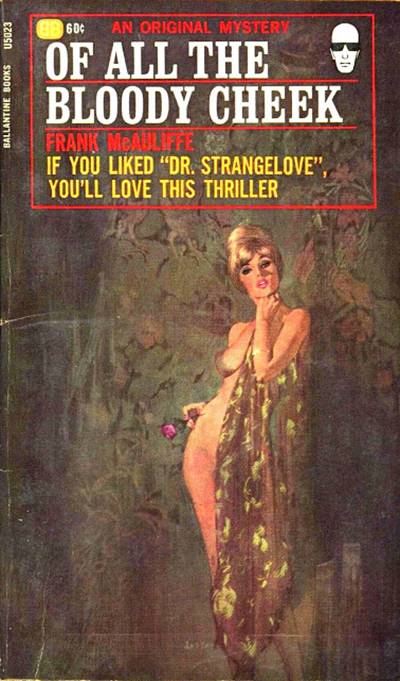

The Lesser Look: “Of All the Bloody Cheek”

Of All the Bloody Cheek, by Frank McAuliffe (Ballantine, 1965). This was the first volume in McAuliffe’s series starring master of disguise and hit man Augustus Mandrell.

READ MORE: Detectives Beyond Borders blogger Peter Rozovsky has composed a number of interesting posts about McAuliffe and Mandrell, all of which can be found here.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 5:37 AM

Thursday, June 7, 2018

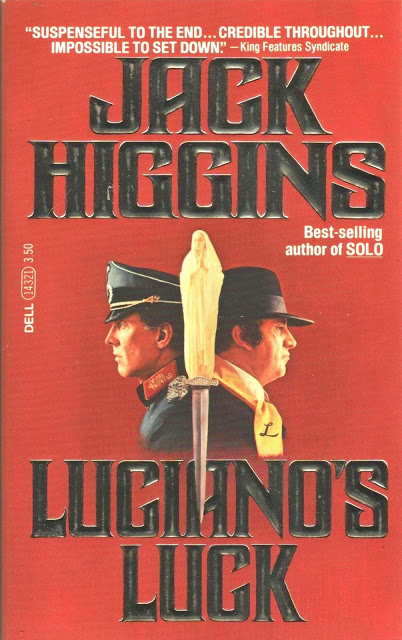

The Lesser Look: “Luciano’s Luck”

Luciano’s Luck, by Jack Higgins (Dell, 1981). The woman on the knife is one of Lesser’s favorite models, Jane Minion.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 5:49 AM

Wednesday, June 6, 2018

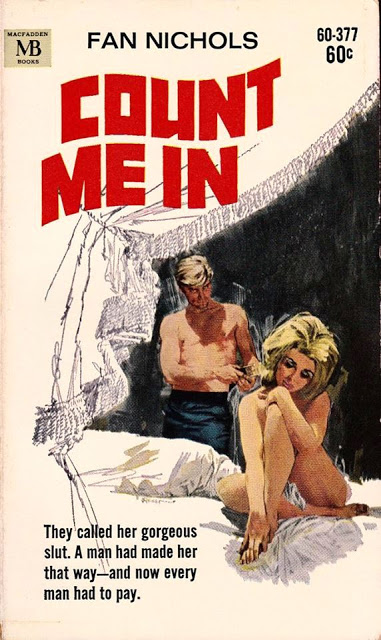

The Lesser Look: “Count Me In”

Count Me In, by Fan Nichols (Macfadden, 1969). Nichols (married name: Frances Nichols Hanna) concocted romance and crime novels during the mid-20th century. Among her other books were Be Silent, Love, One by One, and The Loner.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 7:57 AM

Tuesday, June 5, 2018

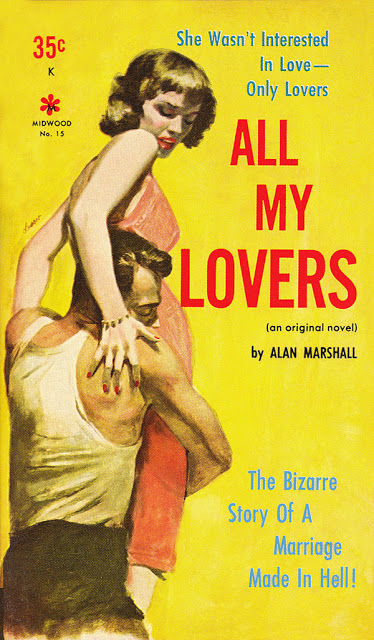

The Lesser Look: “All My Lovers”

All My Lovers, by “Alan Marshall” (Midwood, 1959). Donald E. Westlake wrote several novels for Midwood under the Marshall pseudonym, and this was one of them. In fact, All My Lovers is recorded as Westlake’s first novel, released long before his “official” debut with 1960’s The Mercenaries (aka The Cutie).

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 10:02 AM

Monday, June 4, 2018

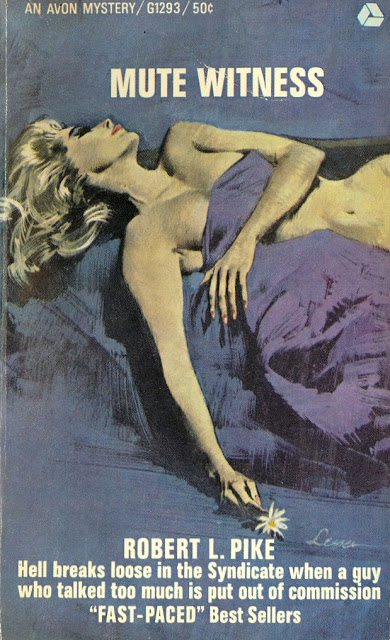

The Lesser Look: “Mute Witness”

Mute Witness, by “Robert L. Pike,” aka Robert L. Fish (Avon, 1966). This is the novel on which the 1968 Steve McQueen film Bullitt was loosely based.

READ MORE: “Robert L. Pike and Bullitt,” by Steve Lewis (Mystery*File); “Cut to the Chase,” by J. Kingston Pierce (The Rap Sheet); “15 Novels That Were Eclipsed by Their Movie Adaptations,” by Nicole Bartner (Den of Geek!).

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 8:04 AM

Sunday, June 3, 2018

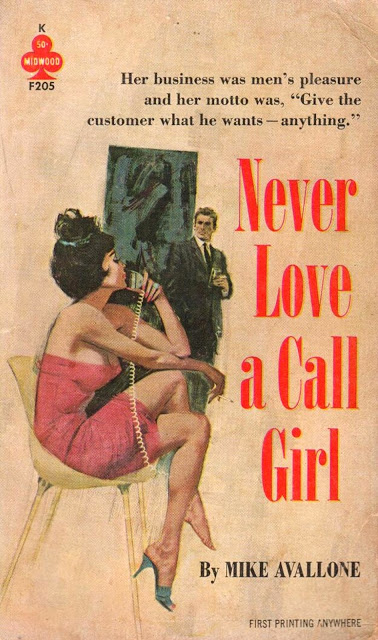

The Lesser Look: “Never Love a Call Girl”

Never Love a Call Girl, by Mike Avallone (Midwood, 1962). The model for this front was again artist Lesser’s wife, Claudia. If you’d like to see the back cover of this novel, click here.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 7:19 AM

Saturday, June 2, 2018

The Lesser Look: “Blue Mascara Tears”

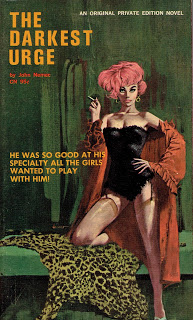

Blue Mascara Tears, by James McKimmey (Ballantine, 1965). According to Lesser, the cover model used in this painting was Lisa Karen, who also features in his cover—shown below—for The Darkest Urge, by John Nemec (Private Edition, 1966).

This is one of many paperback fronts that have been misidentified over the decades as having been painted by Robert McGinnis, while it’s actually Ron Lesser who deserves the credit. When I ask him about such confusions, Lesser says: “I know my work from the late 1960s until 1978 is often compared to Bob’s. I do take that as a compliment. However, if you study my work after 1978 you will see a very different look. It was at that time I switched to oils and I deliberately changed my painting approach, for many reasons. Before 1978, I was using water-based paint—casein white for body, and then designers’ colors, which have more ‘body’ (covering ability) than watercolors, but less than casein.”

He recalls further how he changed his paint mediums over the years: “When I left [Frank J.] Reilly’s class [at New York’s Art Students League], I continued to paint in oil for awhile. All of the paintings I did in class were in oil, so it was natural for me to paint in oil. But because of the influence of McGinnis and [Mitchell] Hooks, paperback publishers were looking for a more modern-style technique than the very ‘painty’ look of oil art … that was very popular since the ’40s. … So I altered my technique away from what I was doing to what was

He recalls further how he changed his paint mediums over the years: “When I left [Frank J.] Reilly’s class [at New York’s Art Students League], I continued to paint in oil for awhile. All of the paintings I did in class were in oil, so it was natural for me to paint in oil. But because of the influence of McGinnis and [Mitchell] Hooks, paperback publishers were looking for a more modern-style technique than the very ‘painty’ look of oil art … that was very popular since the ’40s. … So I altered my technique away from what I was doing to what was

rapidly a changing market in the look of paperback covers. McGinnis used egg tempera which he made himself. Egg tempera uses eggs in the mixture. I tried making this, but the smell from rotting eggs was terrible. I guess I wasn’t doing it right.”

Finally, I ask Lesser a question that has been on my mind and that of others as well: “If I understand correctly, during the 1960s you were brought in occasionally by publishers to work on some series (I’m thinking here particularly of the Carter Brown and John D. MacDonald books) that were known for their McGinnis cover illustrations. It may have been that McGinnis himself was too busy at the time with other projects, but in any case, you were seemingly asked to maintain a continuity of style. And you did a terrific job of it. As a commercial artist, you knew you were beholden to the clients to deliver the sort of covers they wanted. But did it bother you at all that you weren’t given the opportunity in those instances to come up with something showcasing your own approach and ideas?”

To which Lesser responds: “I never felt that I was not painting what came naturally to me at the time … I was never asked to maintain a style. I knew what publishers expected from me in regard to these kind of covers. As I said, it was a natural fit for me.

“I had a long career painting paperbacks. I strongly believe I succeeded because I never gave the art directors problems. Before 1980, the art directors had a lot of power in regard to the selection of the artist, the content of the art, the sketch approval, etc. For whatever reason, that power was ceded to the editorial department during the ’80s. I knew if the art director gave me instructions, it was coming from editorial. There were times I disagreed with the instructions: from my point of view there was an approach that would have made for a better cover than the approach I was given. I would offer my opinion one time only. After that I would obey the wishes of the AD, knowing he had to please editorial. To argue with the AD would embarrass him, because no AD would admit he had very little control over what the editorial department wanted.

“Note: the only [book-publishing] company I worked for that had female art directors was Harlequin.”

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 8:22 AM

Friday, June 1, 2018

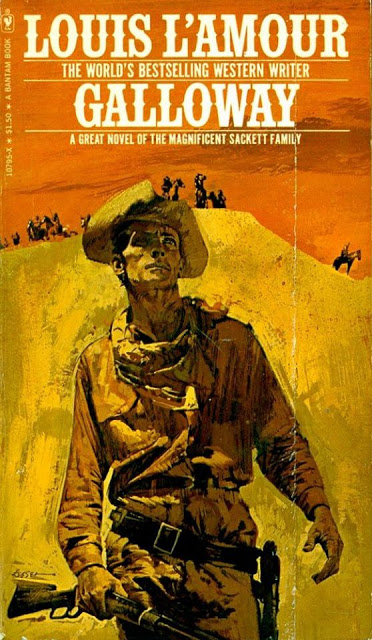

Galloway, by Louis L’Amour (Bantam, 1976).

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 5:23 AM

Thursday, May 31, 2018

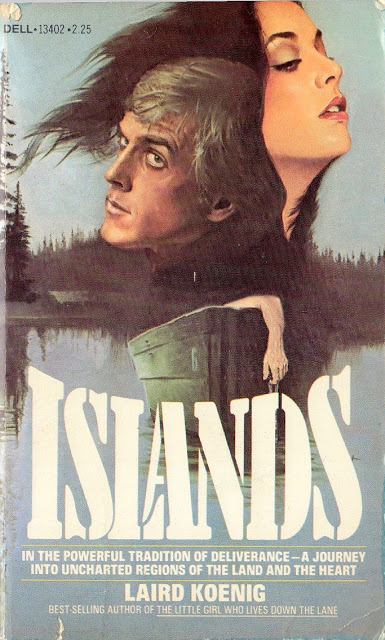

Islands, by Laird Koenig (Dell, 1980).

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 8:21 AM

Wednesday, May 30, 2018

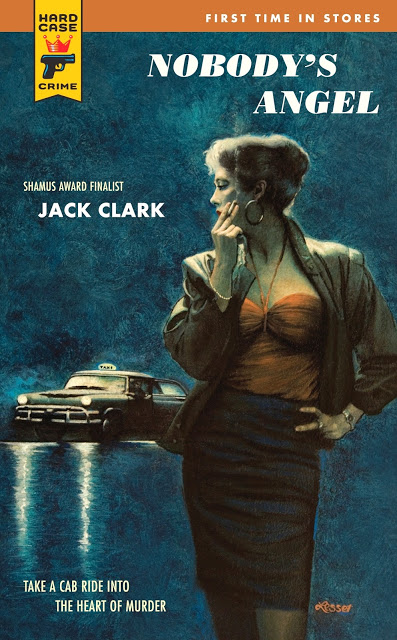

The Lesser Look: “Nobody’s Angel”

Nobody’s Angel, by Jack Clark (Hard Case Crime, 2010).

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 8:25 AM

Tuesday, May 29, 2018

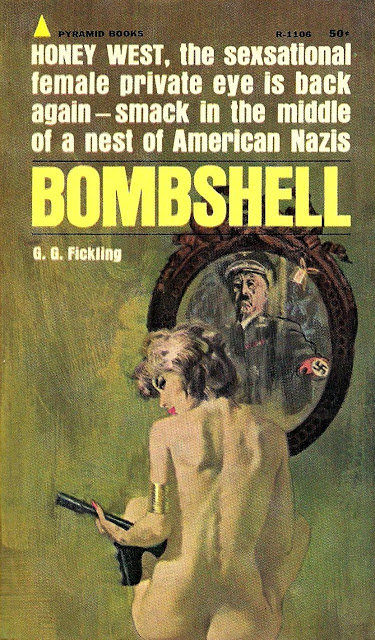

Bombshell, by “G.G. Fickling,” the pseudonym of Gloria and Forest Fickling (Pyramid, 1964). This is the ninth entry in their series starring private eye (later spy) Honey West. The model for this cover was artist Lesser’s wife, Claudia.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 8:02 AM

Monday, May 28, 2018

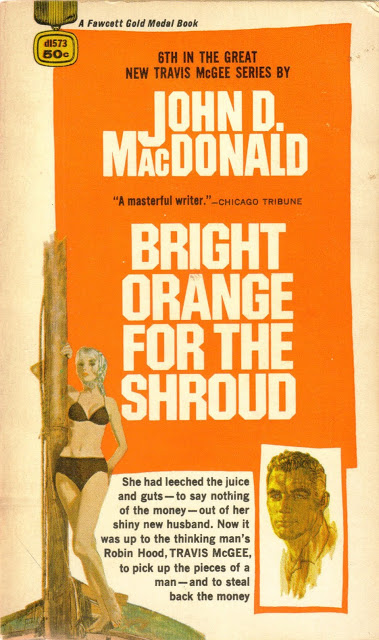

The Lesser Look: “Bright Orange for the Shroud”

Bright Orange for the Shroud, by John D. MacDonald (Fawcett Gold Medal, 1965). This is the sixth entry in MacDonald’s Travis McGee series. The main cover art is by Ron Lesser, but the inset portrait of McGee was done by John McDermott.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 7:57 AM

Sunday, May 27, 2018

The Lesser Look:

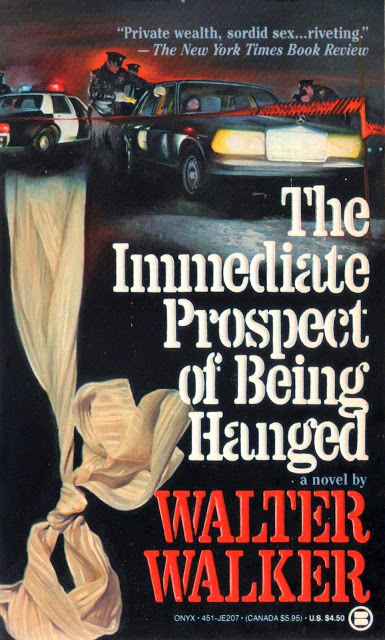

“The Immediate Prospect of Being Hanged”

The Immediate Prospect of Being Hanged,

by Walter Walker (Onyx, 1990).

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 7:15 AM

Saturday, May 26, 2018

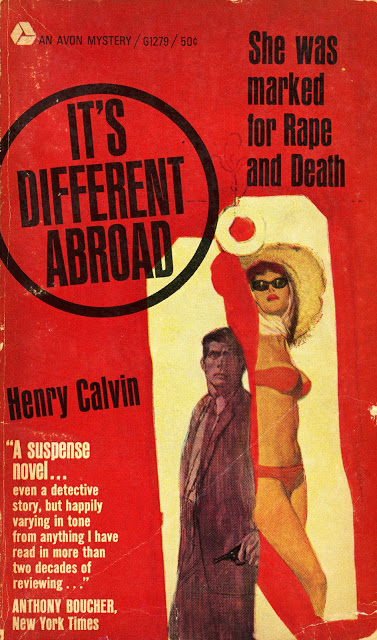

The Lesser Look: “It’s Different Abroad”

It’s Different Abroad, by “Henry Calvin,” a pseudonym used by Scottish journalist-author Clifford Hanley (Avon, 1965).

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 7:35 AM

Friday, May 25, 2018

The Lesser Look: “Think Fast, Ranger!”

Think Fast, Ranger! by Will C. Brown (Dell, 1961).

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 9:42 AM

Thursday, May 24, 2018

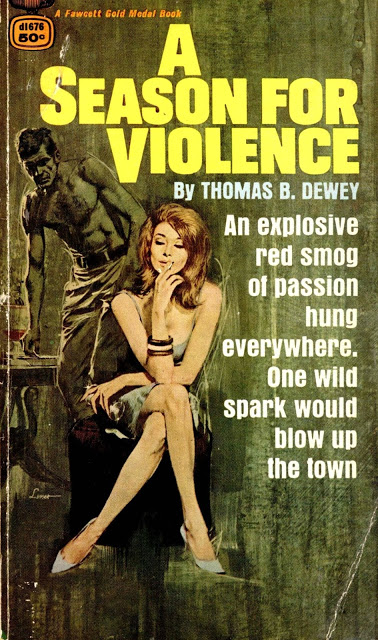

The Lesser Look: “A Season for Violence”

A Season for Violence, by Thomas B. Dewey (Fawcett Gold Medal, 1966). This is a standalone work, not part of Dewey’s justly acclaimed Mac detective series.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 6:56 AM

Wednesday, May 23, 2018

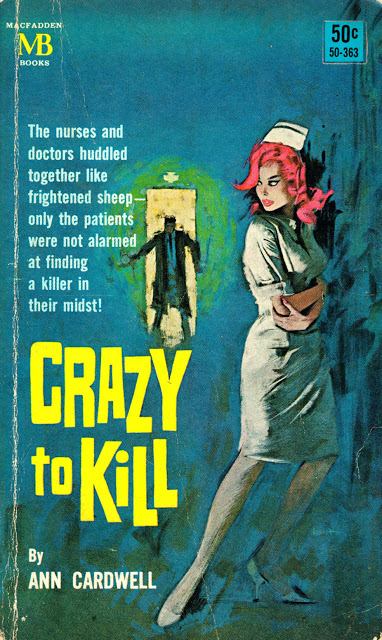

The Lesser Look: “Crazy to Kill”

Crazy to Kill, by “Ann Cardwell,” aka Jean Makins Powley (Macfadden, 1962). Canadian writer Powley produced one other mystery novel, Murder at Calamity House.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 6:20 AM

Tuesday, May 22, 2018

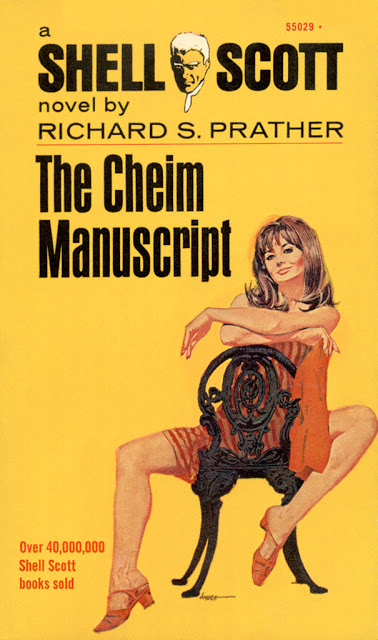

The Lesser Look: “The Cheim Manuscript”

The Cheim Manuscript, by Richard S. Prather (Pocket, 1969). Part of Prather’s long-running Shell Scott private-eye series.

Posted by J. Kingston Pierce at 10:21 AM